Dirk Zoete

Rare Nature 1

2021

pencil on paper, framed

140 x 100 cm

Dirk Zoete

The Cactus Derivatives-8, Thursday, January 9, 2020

2020

(Colored) pencil and pigment on paper, framed

29,7 x 21 cm

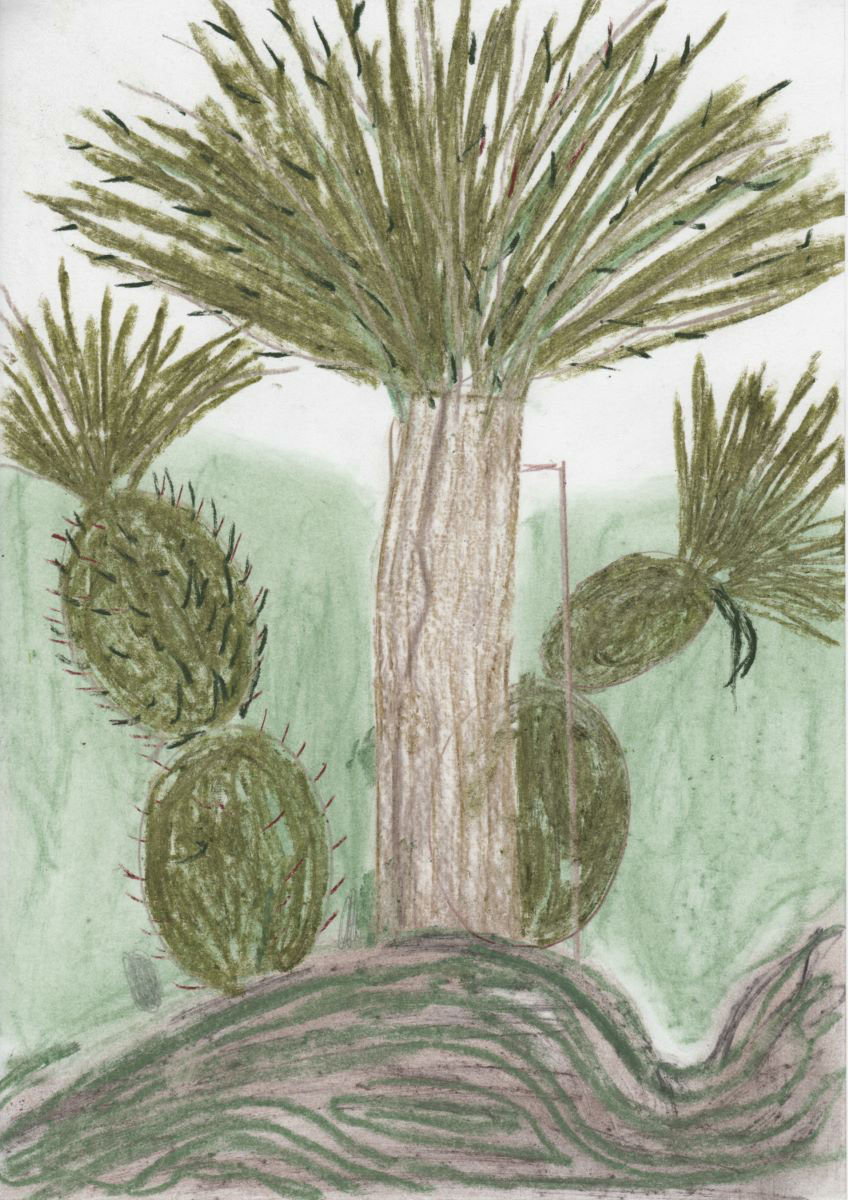

Dirk Zoete

The Cactus Derivatives-2, Monday July 8, 2019

2019

(Colored) pencil and pigment on paper, framed

29,7 x 21 cm

Dirk Zoete

The Cactus Derivatives-21, Wednesday, November 13, 2019

2019

(Colored) pencil and pigment on paper, framed

29,7 x 21 cm

Matthias Dornfeld

Untitled (Flowers)

2017

Oil on canvas

60 × 50 cm

Dirk Zoete

The Cactus Derivatives-5, Sunday July 7, 2019

2019

(Colored) pencil and pigment on paper, framed

29,7 x 21 cm

Matthias Dornfeld

Untitled (Flowers)

2021

Acrylic, gouache and oil on canvas

100 × 70 cm

Dirk Zoete

Hanging Figure 1 - 6

2019

mixed media

245 x 65 x 30 cm

Dirk Zoete

Mirror and model

2017-18

pencil on paper, framed

140 x 100 cm

Matthias Dornfeld

Untitled (Trotzdem)

2021

Oil on MDF

155 × 115 cm

%20%2C%20acrylic%20and%20gouache%20on%20canvas%20%2C%20110%20x%2080%20cm%20%2C%202021.jpeg)

Matthias Dornfeld

Untitled (Portrait)

2021

Acrylic and gouache on canvas

110 × 80 cm

Elen Braga

Elen ou Hubris (detail)

2020

Hand-tufted tapestry

500 × 90 cm

Works

‘Charme Brut’

opening during Brussels Gallery Weekend

At the end of the 1940s, in the wake of a horrific World War, a new kind of art appeared in the Western art scene. It was introduced by the French artist Jean Dubuffet, who called it ‘art brut’. Tellingly, in the same period, ‘brutalist’ architecture reacted against the smooth machine aesthetics of the pre-War period.

At first, Dubuffet had used the term ‘art brut’ to include art of the mentally ill, or visual expressions created within archaic or non-modern societies, or drawings and paintings made by children. The interest in this kind of expressions was not new – already in, amongst others, Gauguin, Matisse, or Picasso, art of archaic or non-Western origin was an important source of inspiration. Paul Klee, on the other hand, was deeply influenced by the amazing Prinzhorn collection of ‘outsider art’, or by children’s drawings. Simultaneously with Dubuffet, the artists of CoBrA were inspired by the same three kinds of ‘alternative’ art creation.

But, after a while, Dubuffet changed his own position vis-à-vis this ‘alternative’ art fundamentally. He started to use the term ‘art brut’ for his own art, at once canceling any distinction between ‘real’ or ‘mature’ or ‘high’ art at the one hand, and ‘outsider’ or ‘naïve’ or ‘folk’ art on the other. This was a radical gesture. Sometimes, an artist has to pass through another medium or discipline, to make it possible that his or her art be revolutionized. This was, for example, the case with Alberto Giacometti. At some point in the 1940s, he got entirely stuck in his sculptural practice. It was through making drawings that his sculpture got liberated from its massiveness.

Something similar happened in Dirk Zoete’s trajectory. Like Klee, Zoete is a draughtsman. His world is built with lines, mostly realized with crayon on paper. But, until some decade ago, those drawings were too much attached to a ‘realistic’ idiom, that is, to some depiction of an observed outer reality in which linear perspective and modulation with light and shadow generate a virtual depth. Zoete liberated his world of lines by making a little theatre, in which he put some miniature objects. He would photograph these scenes, then to make a copy, then to draw on this copy, then to draw on the copy of the latter copy. And so on. With the resulting bunch of copies Zoete would make some wondrous animation film. This process would serve as the basis of a profoundly renewed drawing practice. Somewhat later, the whole process moved from the little theatre to life size. The artist attached all kind of objects or props to his own body, or to that of a model, putting this ‘extended’ body in front of the camera, starting the same kind of copy-and-drawing process as before. This time, that process resulted not only in a series of autonomous drawings, but also in sculptures.

What was it, in this kind of procedure, that revolutionized Dirk Zoete’s poetics? I think this very elementary, concrete and mechanistic process liberated Zoete’s art from a traditional kind of bourgeois individualism. In a ‘realistic’, renaissance-like depiction of the world, the homogeneous virtual space of the image responds to one particular gaze – firstly that of the artist, secondly that of the spectator, as such offering the illusion that one individual can create and master a world.

In a playful and joyful poetics, that reminds one sometimes of Russian constructivist art or theatre, the artist (as well as the spectator) moves out of the center, entering continuous and multifarious

interactions with other creatures or things, being moved as much as moving others, being created as much as creating something.

The representation of a colossal leg is made in hand tufted tapestry by the Brazilian artist Elen Braga. It was part of a gigantic tapestry, depicting a head-to-toe self-portrait of the artist, measuring 24 by 5 meter, weighing 400 kg. It was the first tapestry she ever made. It costed her two years of hard, disciplined, repetitive work. There is a paradoxical tension between this humble work and the personal hubris of someone representing herself on such a scale, and in such a context: during 5 hours, the tapestry was hung from the central vault of the Jubelpark triumphal arch.

As the artist needed financial support to make this project possible, she sold almost all the parts of the tapestry (eyes; mouth; chin; earlobe; elbow; sex; hip curve; …) to her sponsors, as if it were a kind of ex-voto’s. The colossal, as is known to sculptors, responds to other laws than the monumental: above a certain scale, the ideal classical proportions don’t function anymore. Moreover, the production of tapestry allows for much less control than, for example, painting. One is working partly blind, from behind, on a mirrored image, and occasions to correct are very limited. So, the artist has to thrust his or her tracing gesture. The resulting drawing looks quite raw. Braga was inspired by several legendary stories from antiquity. First of all, the story of Arachne, the weaver who challenged Athena, and made a tapestry judged as beautiful as that of the goddess. Moreover, it depicted the kidnapping of Europa by Zeus, the latter in the guise of a bull. As always in Greek mythology, that much human hubris had to be punished mercilessly: Arachne was transformed into a spider.

A second figure is Nebukadnezar II, the greatest Babylonian king. In the Old Testament book of Daniel it is written that this king dreamed about a colossal statue of himself, consisting of 4 metals and clay. This was interpreted by Daniel as a vision of the future, consisting of the rise and collapse of 4 reigns. In later times, until today, images of this Nebukadnezar statue are used as a measuring instrument, or analyzed as predicting the end of times.

Elen Braga didn’t follow any professional art education. The first part of her life consisted mainly in being a gospel singer and, simultaneously, a model, that was put into beauty contests by her mother. She started to make art as an antidote to that. Painting self-portraits led to painting her own body entirely in pink, like a bubblegum phantasy, a primitive body. Like many important performance artists before her, she put this painted body in front of a video camera. At a certain point, she entered into Brazilian ‘fight games’. After being seriously injured, and a long revalidation, she came across the ‘Hercules method’, prescribing a lot of exercises to become as strong as this half-god of antiquity. If Braga creates and completes 12 labors, as Hercules did, will she be as strong as him? Every task is started with a question: is it possible to … ? That’s how she is always working: first the question, then the (choice of) medium.

Like Elen Braga, Matthias Dornfeld didn’t follow any art education. His background consists of a lot of fighting and a lot of struggle. In very thin layers Dornfeld paints on the raw canvas. What he paints has, with time, become more and more reduced. To nothing but the basics, and the fighting.

His work is created far away from any art world issues. He opts for very simple solutions like kids sometimes do, or people who don’t know how to paint. He is interested in painting clichés, like the portrait, with very simple gestures. Those portraits sometimes look very funny, sometimes very dark and deep. Or magical. Dornfeld is the kind of artist who likes and dares to seek the thin border between something and nothing. Going for that edge, when people ask themselves: does he mean this seriously, or is he just playing? But it also functions as a challenge for himself: will it fall down, or will it hold, even being almost nothing? So: he is fighting while putting himself in the most fragile position. He doesn’t want to work in series. The next step denies the one before. But he is always seeking for archetypes. To me, these paintings by Matthias Dornfeld are as much object as they are image. They function as if they were icons in a godless world.

Frank Maes

September 9 - October 16, 2021

BRUSSELS

Charme Brut

Dirk Zoete

Elen Braga

Matthias Dornfeld